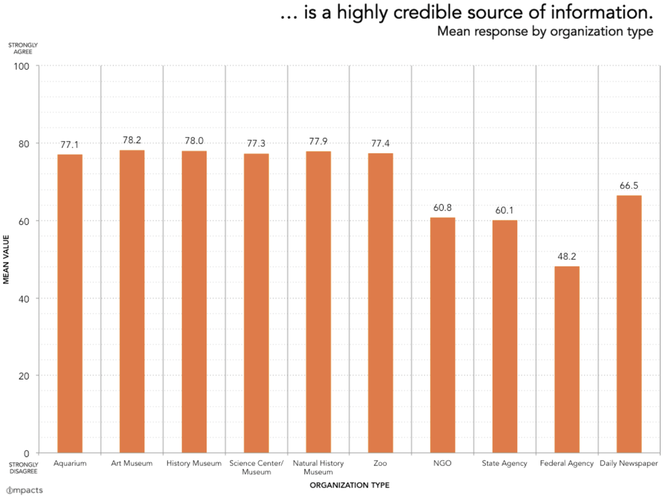

Salvator Mundi, a long-lost painting that some say is by Leonardo da Vinci. Christie's claimed it was a 'signature work'. It sold for $400 million. Image credit, Christie's. Salvator Mundi, a long-lost painting that some say is by Leonardo da Vinci. Christie's claimed it was a 'signature work'. It sold for $400 million. Image credit, Christie's. You may have heard about the painting that sold for $400 million ($450 million with fees) last November; the largest sum ever paid for a single artwork at a public auction. Astounding. The sale was for the 'Salvator Mundi', believed to be a long-lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci. The auction lasted for nineteen minutes. Some say it was like an intense theatre performance, with gasps, thunderous applause and cheers when the final gavel announced…’sold [to the anonymous bidder on the telephone] for $400 million’. The 'Salvator Mundi' sale shattered the previous record of $179.4 million for a Picasso in 2015; it created tsunami-type waves in the elite art community. But for regular people, an art enthusiast and museum-goer like me, it seemed inconsequential, far removed from my world. But when listening to a podcast with Ben Lewis, art critic and historian discussing his book The Last Leonardo: The Secret Lives of the Word’s Most Expensive Painting, and after reading his book, I changed my mind. The painting’s story, as told in The Last Leonardo from its humble discovery in 2008, to clandestine meetings, two restorations, to an exhibition at London’s National Gallery, to a smashing sale, reveals much about art and museums. I see the story as a catalyst for us to think more about arts value and role in society, and about what cultural institutions say, promote and stand for. There’s a need for us to be more objective, to ask more questions, consider and discuss what institutions are telling us about their collections and exhibitions. The trust we have in cultural institutions is high, yet we need to consider how they influence and shape our perceptions about art, historical events, people and ideas. Below I share three ideas about what we can learn from the sale of the most expensive painting in the world. A Brief Background In The Last Leonardo, Lewis writes of the 'Salvator Mundi'’s tumultuous journey from it’s discovery by two unassuming art dealers who found it (in disastrous condition) in an online auction catalogue and bought it for $1,175. Lewis then takes us back in time, untangling the painting’s complicated ownership history. That’s the crux of story—is the 'Salvator Mundi' a Leonardo or not? It’s complicated ownership has made it difficult to determine conclusively whether it was by Leonardo, or by one or more of his workshop assistants. Lewis also writes of the lack of consensus among Leonardo experts. Yet, despite the inconclusive accreditation, Christie’s promoted it as a Leonardo, and the “greatest artistic rediscovery of the 20th century” (Rodriguez, 2017). London’s National Gallery Involvement is Key to the Story A critical part of the story is the role London's National Gallery played. In 2008 curator Luke Syson invited five leading Leonardo scholars to view and discuss the 'Salvator Mundi' off-the-record. At this point the painting had already undergone the first of its two restorations. Nothing was formally recorded of the meeting or shared publicly, but three years after the meeting the National Gallery issued a press release stating that experts had met and verified that the 'Salvator Mundi' was indeed by Leonardo. Yet Lewis’s research determined that “The final score from the National Gallery meeting seems to have been two Yeses, one No, and two No Comments”. One of the experts at the meeting, Dr. Carmen Bamabach was quoted in National Gallery’s exhibition catalogue that she was among the scholars who had attributed the work to Leonardo; however after its publication Bamabachpu stated publicly that she had never endorsed the painting, nor was formally asked to (Alberge, 2019). After the press release, the National Gallery launched a Leonardo exhibit in 2011- 2012 featuring the 'Salvator Mundi' as unequivocally a signature work of Leonardo. This exhibition turned out to be instrumental in its two sales that followed. The first to Dmitry Rybolovelev, who bought the painting via an art dealer who said, “if it hadn’t been in that exhibition it would have been impossible to sell the painting” (Lewis, p 169). And the second at Christie’s, which would not have ever transpired had it not been in the National Gallery’s exhibition.  'Salvator Mundi' revealed at the Christie's press preview in New York City. Christie's launched an unprecedented campaign, hiring an outside advertising agency for the first time ever (Kinsella, 2019). Image: Christie's 'Salvator Mundi' revealed at the Christie's press preview in New York City. Christie's launched an unprecedented campaign, hiring an outside advertising agency for the first time ever (Kinsella, 2019). Image: Christie's Three Takeaways from the Marketing & Sale of the Most Expensive Painting in the World 1) We’re Targets of Marketing Christie’s launched an uncharacteristic splashy, sexy, “multi-pronged [marketing] campaign” to sell the Salvator Mundi. It seemed similar to what a car company might do for a new car model launch. The auction house spared no expense for what they labeled “the Last da Vinci” including an international multi-city tour, a slick show for the press preview, a polished youtube video and more. Christie’s strategy is a reminder that culture and the arts are not insulated from sales and marketing. It means that we are part of an institutional marketing system—we are the target customers, the ones being influenced, persuaded. Museums, cultural sites, zoos, parks, music, dance and theatre venues, are all marketers vying for our time and money. They need our attendance, our participation, our resources. But this doesn’t mean these institutions are bad, evil or underhanded—marketing and promotion are necessary strategies for any public-serving organization. They need to communicate what they offer, describe how they can meet a need of their target audience. Branding, another aspect of marketing is also critical to cultural institutions; they need to project an image that represents their values in order to attract visitors, potential members, donors, employees, even scholars. To that end, institutions carefully craft what they communicate to the public in press releases, on websites and social media, in newsletters, catalogues, also within the museum—museum labels, signs, and other media used to describe objects and exhibitions. As part of a system then, we as customers on the receiving end need to be aware of what’s going on—that cultural institutions use strategies just like any other business or organization to influence, persuade. Sometimes there is bias, or there’s a narrow, one-sided perspective. Sometimes there is missing information that is key to a deeper appreciation or understanding. This suggests we need to be aware, ask questions, consider multiple points of view, and consider information that might be left out, intentionally or not. We need to question or challenge institutions about what they present and messages they convey—more so if it’s controversial, appears biased, or seems wrong. We are part of the conversation; we’re not passive recipients who trust blindly. 2) We need to Demand More Transparency From Cultural Institutions In keeping with our marketing discussion we could argue that the 'Salvator Mundi' featured in the National Gallery’s Leonardo Exhibition in 2011-2012 was a marketing tool for the museum and perhaps unintentionally for Christie’s. The National Gallery had a blockbuster show—tickets were sold out (the museum extended their hours to 10 pm to accommodate the demand) and they likely made a considerable sum in Leonardo-themed merchandise sales. Did London National Gallery Abuse our Trust? What’s critical is to consider how the 'Salvator Mundi' was presented to the public. The public’s trust in museums is higher than for newspapers or government agencies (see chart below), yet the National Gallery despite the painting’s questionable attribution and several red flags about the paintings origins, presented the painting as an authentic Leonardo. The museum didn’t give any of the backstory, the possibility that its authenticity was in question. They didn’t give visitors an opportunity to engage in discussion or dialogue that the art community was having. It short-changed the visitor—they abused the inherent trust museums-visitors have in cultural institutions. They also missed an opportunity for deeper engagement, for discussion and visitor involvement. This is what museums should do, encourage dialogue, thought and consideration. I suggest there needs to be more transparency in our cultural places. There are other examples of museums withholding information from visitors, like the Elgin Marbles saga at the British Museum, others who have (or had) items in their collection that may be stolen goods or obtained from questionable sources, or still others that present one-sided viewpoints about historical events and fail to include visitors in the discussion. Progress has being made, but there’s a way to go. We need to demand more from our cultural institutions. 3) Market Value of an Artwork Doesn’t Equate with Enjoyment and Meaning If a painting sells for $400 million does that make it ‘better’ than a painting that sells for $1 million? What about a work by an unknown artist versus a Picasso? It’s an interesting question especially when a work or works by an artist are shown in a museum and highlighted as a masterpiece(s). The Louvre Abu Dubai museum for instance had planned a show around the Salvator Mundi (but it was cancelled). These types of exhibits send a message about value—that a work that is purchased for a hefty sum, or a work is by an artist who’s work commands high values in auctions, or even an artist that a celebrity likes for instance, is inherently better. Which is why we need to separate art from external factors—make it about our own experience—to view and appreciate art from the perspective of how it makes us feel and think. I was reminded of this on a visit to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York city two years ago. I was in the gallery showing works of artists of the 20th century. There were works by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in the same room; there were text labels describing the paintings by Picasso—quite in-depth descriptions, yet there were no descriptions on labels of Braque’s work, except for the work’s title and date. I thought it strange; it sent a message--that Picasso’s works were more worthy than Braque’s. As readers already know, art has value not measured in dollars—how an artwork affects individuals is unique, personal. That makes it a challenge for museums to walk the line between highlighting artists who’s work is highly valued on the market versus those who are not—this is more applicable to large art museums who have access to more robust collections. Yet the majority of museums, do do an excellent job of featuring artists who are not as well-known, who highlight work that is unique and interesting—which is what cultural institutions need to do more of, to help people see that art is about how it makes you feel—to experience and consider an idea or message in the work. Conclusion I’m grateful for Ben Lewis for the work he did on this story, for his comprehensive book The Last Leonardo. It reads like an art thriller, but more importantly he pulled a curtain back to reveal behind-the-scenes events that go on in museums and the art world. It’s also a reminder of our role in the story, how we need to challenge, question and think what institutions of all types present to us, and how we need to enjoy art on our terms. References/More to Explore

Comments are closed.

|

Museums for Real is a blog with insights and ideas on how to make museums relevant and enjoyable for everyone.

|