Salvator Mundi, a long-lost painting that some say is by Leonardo da Vinci. Christie's claimed it was a 'signature work'. It sold for $400 million. Image credit, Christie's. Salvator Mundi, a long-lost painting that some say is by Leonardo da Vinci. Christie's claimed it was a 'signature work'. It sold for $400 million. Image credit, Christie's. You may have heard about the painting that sold for $400 million ($450 million with fees) last November; the largest sum ever paid for a single artwork at a public auction. Astounding. The sale was for the 'Salvator Mundi', believed to be a long-lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci. The auction lasted for nineteen minutes. Some say it was like an intense theatre performance, with gasps, thunderous applause and cheers when the final gavel announced…’sold [to the anonymous bidder on the telephone] for $400 million’. The 'Salvator Mundi' sale shattered the previous record of $179.4 million for a Picasso in 2015; it created tsunami-type waves in the elite art community. But for regular people, an art enthusiast and museum-goer like me, it seemed inconsequential, far removed from my world. But when listening to a podcast with Ben Lewis, art critic and historian discussing his book The Last Leonardo: The Secret Lives of the Word’s Most Expensive Painting, and after reading his book, I changed my mind. The painting’s story, as told in The Last Leonardo from its humble discovery in 2008, to clandestine meetings, two restorations, to an exhibition at London’s National Gallery, to a smashing sale, reveals much about art and museums. I see the story as a catalyst for us to think more about arts value and role in society, and about what cultural institutions say, promote and stand for. There’s a need for us to be more objective, to ask more questions, consider and discuss what institutions are telling us about their collections and exhibitions. The trust we have in cultural institutions is high, yet we need to consider how they influence and shape our perceptions about art, historical events, people and ideas. Below I share three ideas about what we can learn from the sale of the most expensive painting in the world. A Brief Background In The Last Leonardo, Lewis writes of the 'Salvator Mundi'’s tumultuous journey from it’s discovery by two unassuming art dealers who found it (in disastrous condition) in an online auction catalogue and bought it for $1,175. Lewis then takes us back in time, untangling the painting’s complicated ownership history. That’s the crux of story—is the 'Salvator Mundi' a Leonardo or not? It’s complicated ownership has made it difficult to determine conclusively whether it was by Leonardo, or by one or more of his workshop assistants. Lewis also writes of the lack of consensus among Leonardo experts. Yet, despite the inconclusive accreditation, Christie’s promoted it as a Leonardo, and the “greatest artistic rediscovery of the 20th century” (Rodriguez, 2017). London’s National Gallery Involvement is Key to the Story A critical part of the story is the role London's National Gallery played. In 2008 curator Luke Syson invited five leading Leonardo scholars to view and discuss the 'Salvator Mundi' off-the-record. At this point the painting had already undergone the first of its two restorations. Nothing was formally recorded of the meeting or shared publicly, but three years after the meeting the National Gallery issued a press release stating that experts had met and verified that the 'Salvator Mundi' was indeed by Leonardo. Yet Lewis’s research determined that “The final score from the National Gallery meeting seems to have been two Yeses, one No, and two No Comments”. One of the experts at the meeting, Dr. Carmen Bamabach was quoted in National Gallery’s exhibition catalogue that she was among the scholars who had attributed the work to Leonardo; however after its publication Bamabachpu stated publicly that she had never endorsed the painting, nor was formally asked to (Alberge, 2019). After the press release, the National Gallery launched a Leonardo exhibit in 2011- 2012 featuring the 'Salvator Mundi' as unequivocally a signature work of Leonardo. This exhibition turned out to be instrumental in its two sales that followed. The first to Dmitry Rybolovelev, who bought the painting via an art dealer who said, “if it hadn’t been in that exhibition it would have been impossible to sell the painting” (Lewis, p 169). And the second at Christie’s, which would not have ever transpired had it not been in the National Gallery’s exhibition.  'Salvator Mundi' revealed at the Christie's press preview in New York City. Christie's launched an unprecedented campaign, hiring an outside advertising agency for the first time ever (Kinsella, 2019). Image: Christie's 'Salvator Mundi' revealed at the Christie's press preview in New York City. Christie's launched an unprecedented campaign, hiring an outside advertising agency for the first time ever (Kinsella, 2019). Image: Christie's Three Takeaways from the Marketing & Sale of the Most Expensive Painting in the World 1) We’re Targets of Marketing Christie’s launched an uncharacteristic splashy, sexy, “multi-pronged [marketing] campaign” to sell the Salvator Mundi. It seemed similar to what a car company might do for a new car model launch. The auction house spared no expense for what they labeled “the Last da Vinci” including an international multi-city tour, a slick show for the press preview, a polished youtube video and more. Christie’s strategy is a reminder that culture and the arts are not insulated from sales and marketing. It means that we are part of an institutional marketing system—we are the target customers, the ones being influenced, persuaded. Museums, cultural sites, zoos, parks, music, dance and theatre venues, are all marketers vying for our time and money. They need our attendance, our participation, our resources. But this doesn’t mean these institutions are bad, evil or underhanded—marketing and promotion are necessary strategies for any public-serving organization. They need to communicate what they offer, describe how they can meet a need of their target audience. Branding, another aspect of marketing is also critical to cultural institutions; they need to project an image that represents their values in order to attract visitors, potential members, donors, employees, even scholars. To that end, institutions carefully craft what they communicate to the public in press releases, on websites and social media, in newsletters, catalogues, also within the museum—museum labels, signs, and other media used to describe objects and exhibitions. As part of a system then, we as customers on the receiving end need to be aware of what’s going on—that cultural institutions use strategies just like any other business or organization to influence, persuade. Sometimes there is bias, or there’s a narrow, one-sided perspective. Sometimes there is missing information that is key to a deeper appreciation or understanding. This suggests we need to be aware, ask questions, consider multiple points of view, and consider information that might be left out, intentionally or not. We need to question or challenge institutions about what they present and messages they convey—more so if it’s controversial, appears biased, or seems wrong. We are part of the conversation; we’re not passive recipients who trust blindly. 2) We need to Demand More Transparency From Cultural Institutions In keeping with our marketing discussion we could argue that the 'Salvator Mundi' featured in the National Gallery’s Leonardo Exhibition in 2011-2012 was a marketing tool for the museum and perhaps unintentionally for Christie’s. The National Gallery had a blockbuster show—tickets were sold out (the museum extended their hours to 10 pm to accommodate the demand) and they likely made a considerable sum in Leonardo-themed merchandise sales. Did London National Gallery Abuse our Trust? What’s critical is to consider how the 'Salvator Mundi' was presented to the public. The public’s trust in museums is higher than for newspapers or government agencies (see chart below), yet the National Gallery despite the painting’s questionable attribution and several red flags about the paintings origins, presented the painting as an authentic Leonardo. The museum didn’t give any of the backstory, the possibility that its authenticity was in question. They didn’t give visitors an opportunity to engage in discussion or dialogue that the art community was having. It short-changed the visitor—they abused the inherent trust museums-visitors have in cultural institutions. They also missed an opportunity for deeper engagement, for discussion and visitor involvement. This is what museums should do, encourage dialogue, thought and consideration. I suggest there needs to be more transparency in our cultural places. There are other examples of museums withholding information from visitors, like the Elgin Marbles saga at the British Museum, others who have (or had) items in their collection that may be stolen goods or obtained from questionable sources, or still others that present one-sided viewpoints about historical events and fail to include visitors in the discussion. Progress has being made, but there’s a way to go. We need to demand more from our cultural institutions. 3) Market Value of an Artwork Doesn’t Equate with Enjoyment and Meaning If a painting sells for $400 million does that make it ‘better’ than a painting that sells for $1 million? What about a work by an unknown artist versus a Picasso? It’s an interesting question especially when a work or works by an artist are shown in a museum and highlighted as a masterpiece(s). The Louvre Abu Dubai museum for instance had planned a show around the Salvator Mundi (but it was cancelled). These types of exhibits send a message about value—that a work that is purchased for a hefty sum, or a work is by an artist who’s work commands high values in auctions, or even an artist that a celebrity likes for instance, is inherently better. Which is why we need to separate art from external factors—make it about our own experience—to view and appreciate art from the perspective of how it makes us feel and think. I was reminded of this on a visit to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York city two years ago. I was in the gallery showing works of artists of the 20th century. There were works by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in the same room; there were text labels describing the paintings by Picasso—quite in-depth descriptions, yet there were no descriptions on labels of Braque’s work, except for the work’s title and date. I thought it strange; it sent a message--that Picasso’s works were more worthy than Braque’s. As readers already know, art has value not measured in dollars—how an artwork affects individuals is unique, personal. That makes it a challenge for museums to walk the line between highlighting artists who’s work is highly valued on the market versus those who are not—this is more applicable to large art museums who have access to more robust collections. Yet the majority of museums, do do an excellent job of featuring artists who are not as well-known, who highlight work that is unique and interesting—which is what cultural institutions need to do more of, to help people see that art is about how it makes you feel—to experience and consider an idea or message in the work. Conclusion I’m grateful for Ben Lewis for the work he did on this story, for his comprehensive book The Last Leonardo. It reads like an art thriller, but more importantly he pulled a curtain back to reveal behind-the-scenes events that go on in museums and the art world. It’s also a reminder of our role in the story, how we need to challenge, question and think what institutions of all types present to us, and how we need to enjoy art on our terms. References/More to Explore

More than ever people are turning to podcasts as a source for ‘edutainment’. This year it’s estimated that twenty-two million people in the US will tune in weekly to podcasts (Infinite Dial, 2019). That’s a ton! Granted, not all those millions are seeking episodes with the education slant, yet there are great numbers who seek both entertainment and education and some (like me) are looking for arts and museum shows. Yet finding them is a challenge—quality podcasts in the museum and cultural arts realm are scarce. But I found a handful; I shared my favorite five in an article in April and since then I’ve found another three I share here. They’re all quite different, but each ranks high in quality of content and delivery. 1. National Gallery of Art Podcast This show features lectures on the collection and special exhibitions of the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Washington, D.C. I’ve listened to several episodes in the past and found them somewhat dry (episodes are recordings of lectures delivered to audiences at the museum, without the benefit of visuals). However, I’ve re-discovered the show. It’s now one of my favorites due to the 14-part series with NGA’s senior lecturer, David Gariff. The lecture series, Celebrating the East Building: 20th-Century Art coincides with the museum’s newly renovated East building featuring its 20th century collection in a chronological story. Even without images the hour-long episodes are excellent—engaging, interesting, sometimes funny. Garriff doesn’t read from a script but tells stories of the artists and various art movements. Some of his best episodes: German Expressionism and Degenerate Art and Henri Matisse and Fauvism. These episodes along with the others were posted in August 2018. I typically listen on-the-go, but if you are able to access the web while listening, you can look up the images of artworks Gariff refers to. Check out www.nga.gov or google. The visuals enrich the experience but aren’t necessary; I learned a great deal just by listening.  Podcast logo Podcast logo 2. Museum Archipelago A terrific show that delves into issues and challenges with museums and cultural institutions with bite-sized episodes, no more than fifteen minutes each. The host, Ian Elsner interviews museum founders, directors and people working in the museum world. What’s unique is Elsner seeks out smaller institutions, museums outside of the United States, and people working in the museum-world, some not associated with large institutions. Perspectives shared are fresh, and real. Three of my favorite episodes: #46, with Vessela Gercheva, Director of the first children’s museum in Bulgaria, #45 with Margaret Middleton, an independent museum professional who designs children’s exhibits. Her perspective on making museums approachable for both visitors and people working in the field is thought-provoking. Episode #61 features Dr. Jody Steele who manages Australia’s Port Historical Authority and sites like the Female Factory which tells the story of female convicts transported from Britain to Australia in the 1800s. Really interesting. “The show believes that no museum is an island and that museums are not neutral” — museumarchipelao.com  Podcast logo Podcast logo 3. Great Lives, BBC Radio 4 Great Lives is not about art or museums specifically but features biographies of ‘great’ people of history—individuals from antiquity to those who have recently passed. Episodes, thirty-minutes in length, are never dull, are always interesting. I love the host, Matthew Parker, who interviews a guest (usually famous in some way or another) who nominates a ‘great life’ along with an expert, someone with deep knowledge of the nominee. Episodes have featured artists, like the episode on Marcel Duchamp, nominated by artist Cornelia Parker, with the expert, a Professor of the History of Art at the Royal Academy in London (aired December 12, 2017). Others have highlighted patrons of the arts, like Catherine de Medici (April 18, 2019) and Catherine the Great, (June 1, 2018). There are numerous episodes on authors, musicians and one of my favorites—the episode on Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein (May 17, 2019). Related

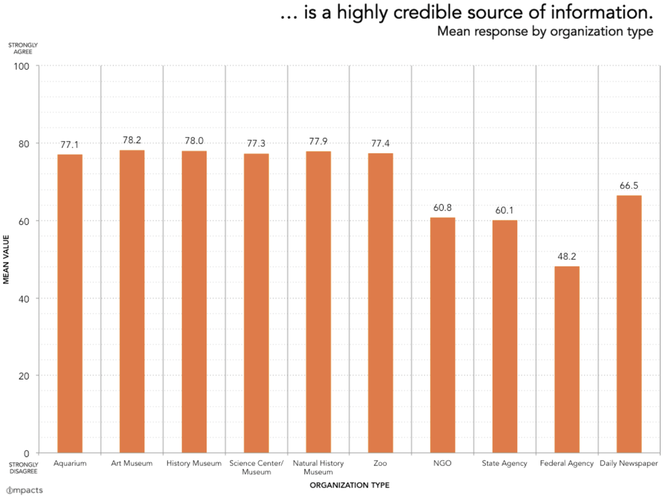

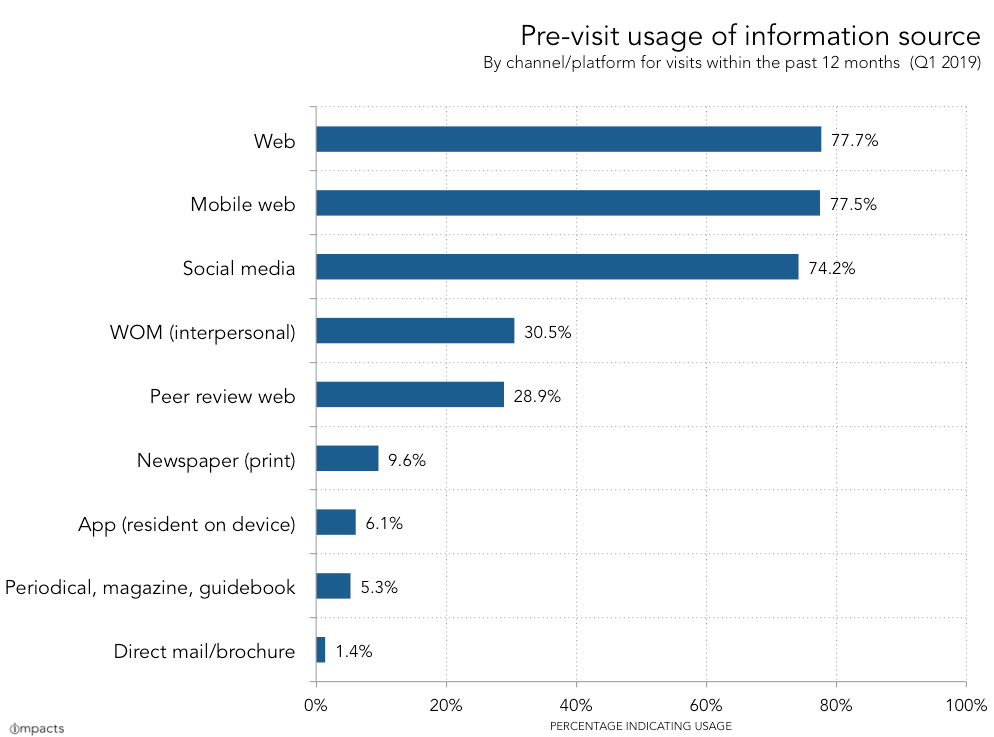

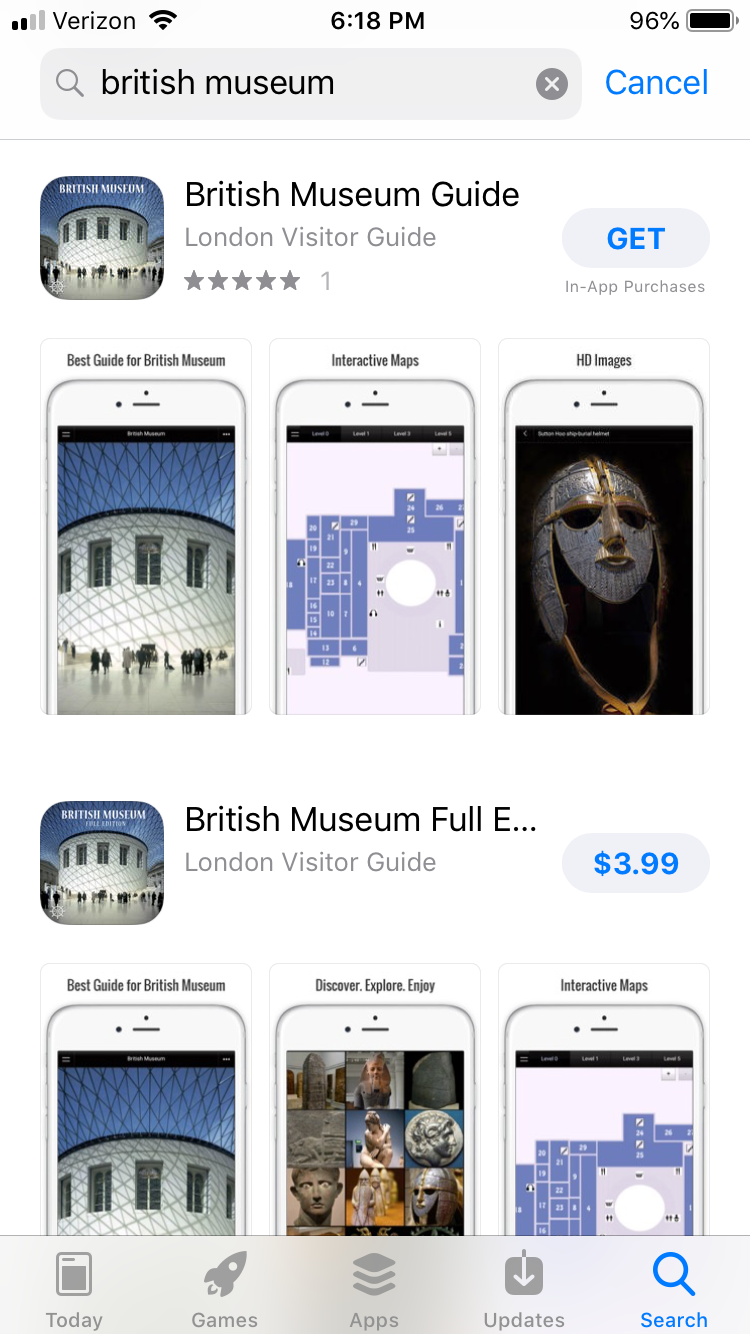

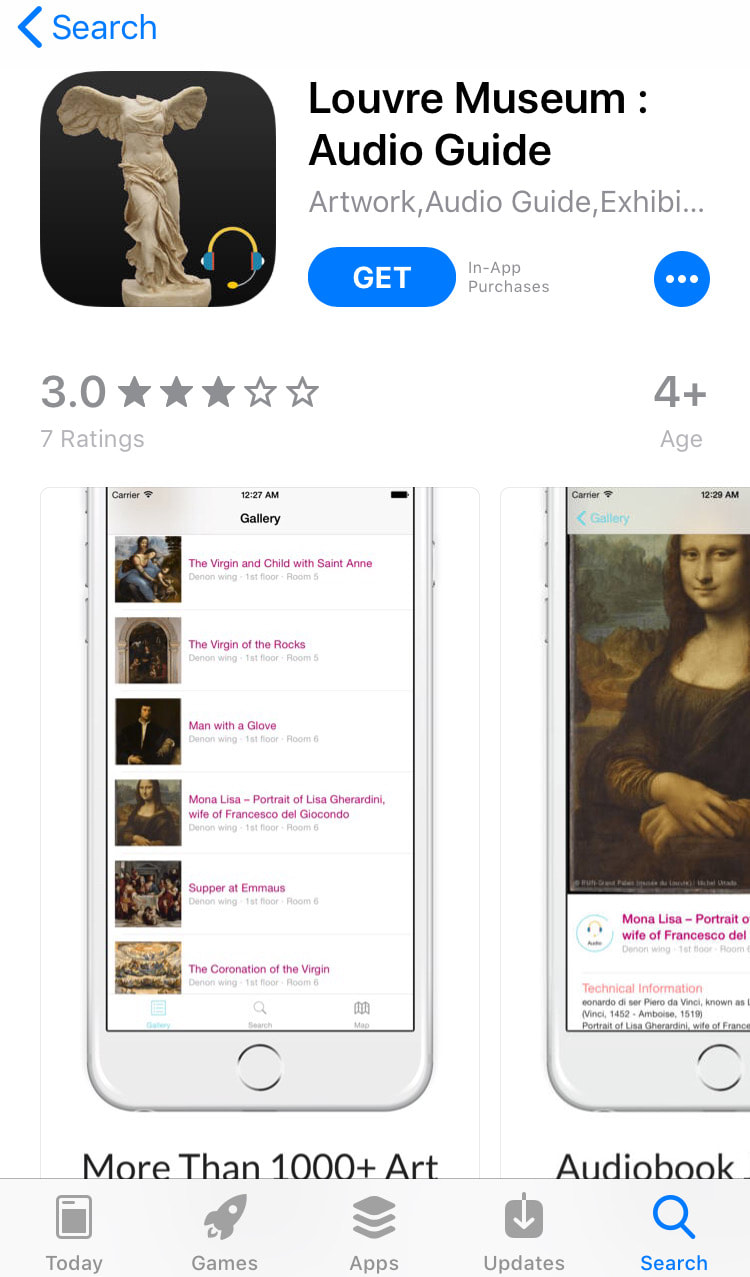

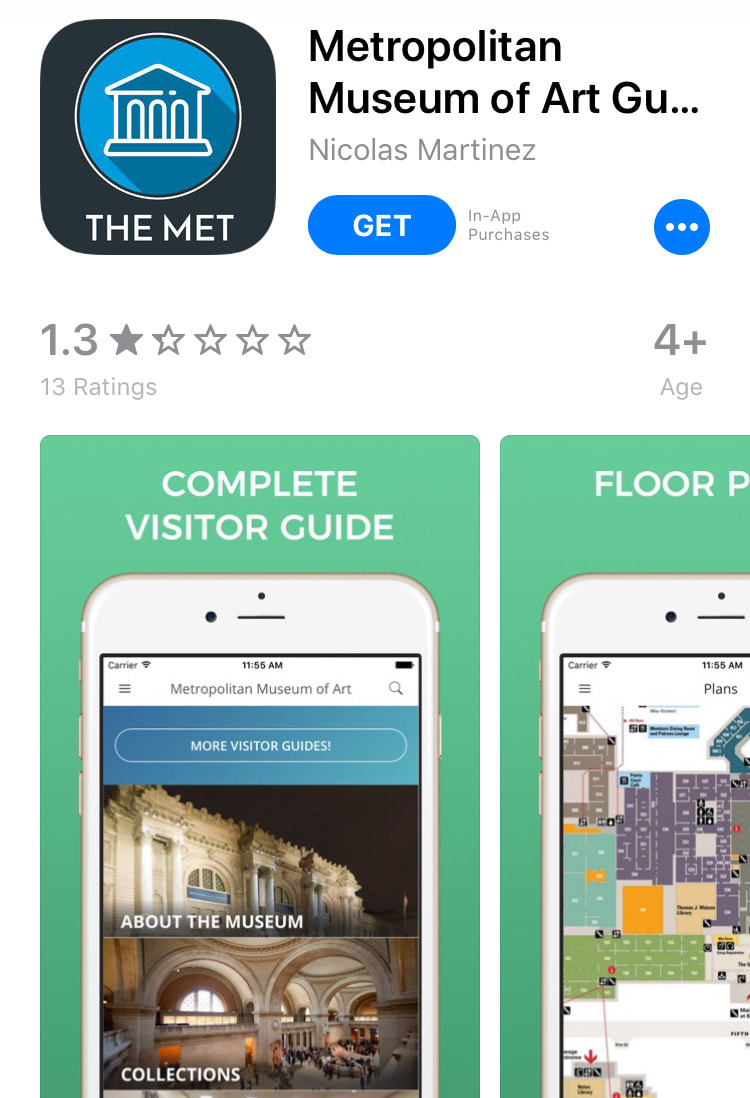

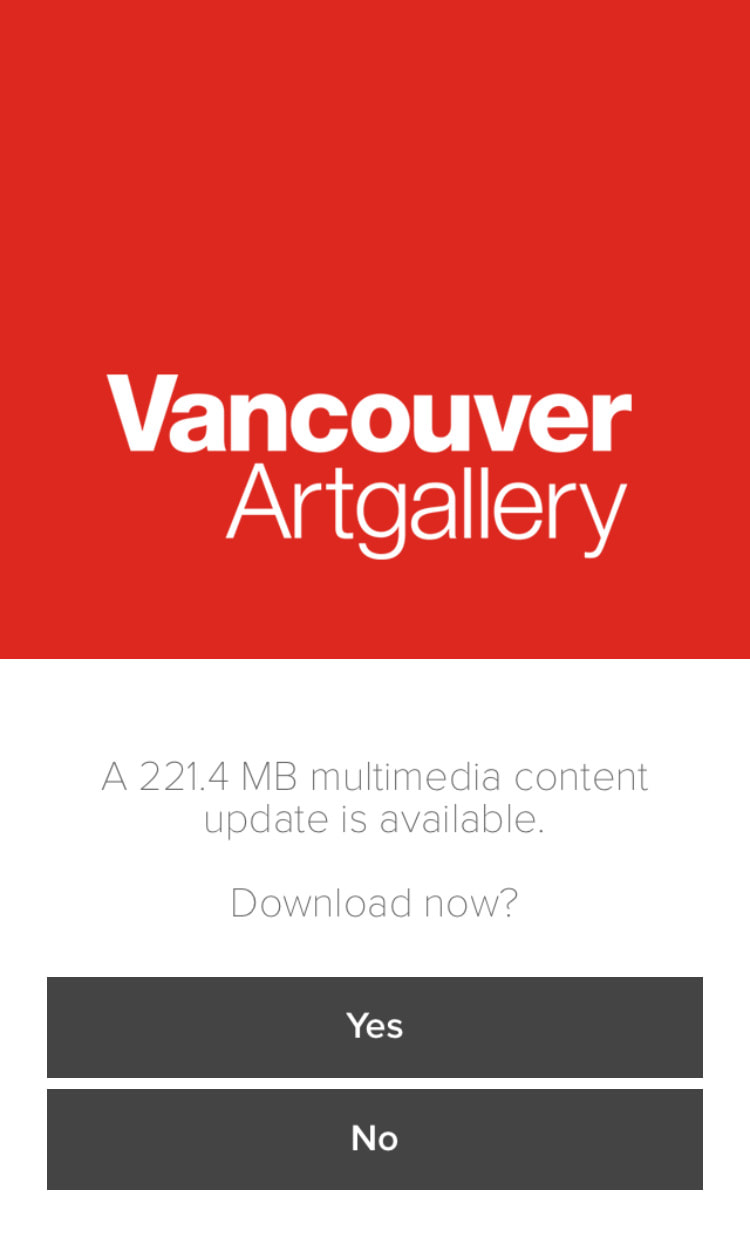

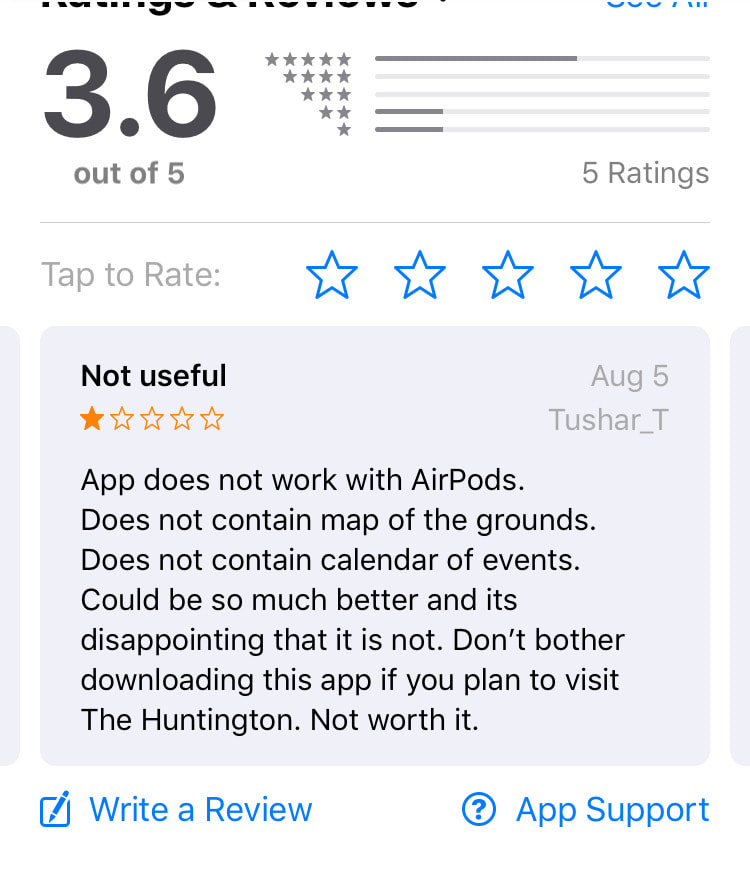

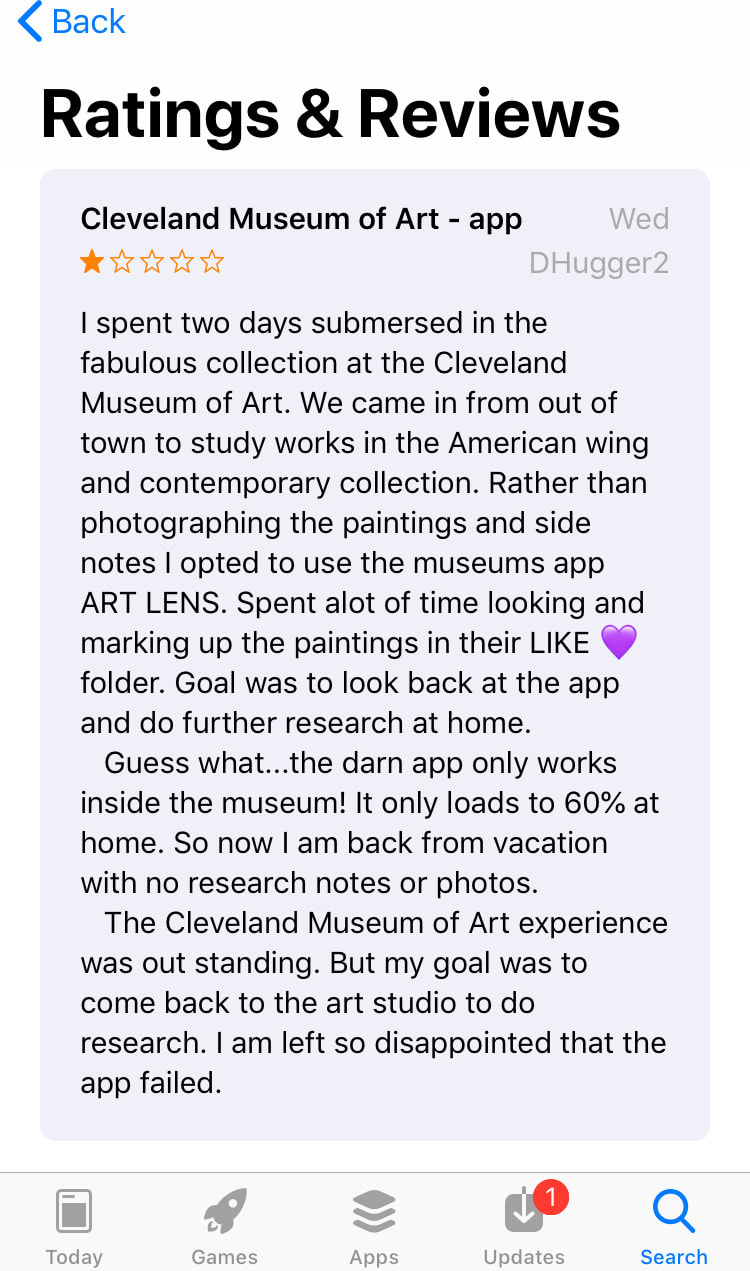

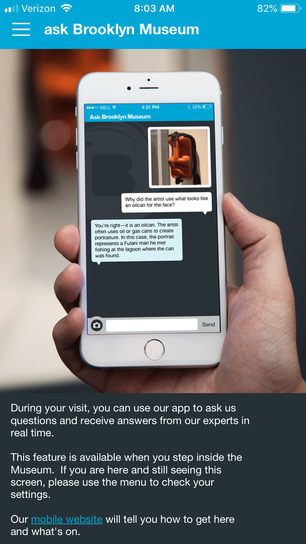

Smartphone apps are BIG; people love them—over 200 billion were downloaded in 2018. I love apps too. I also love museums; yet there’s only a couple of museum apps I love. This article delves into museum apps: the research on visitors' perspectives, key challenges, and reviews a selection of good and bad examples, as well as recommendations on how to fix them. First things first, museums should consider apps for a few reasons, primarily because people are increasing their use of mobile internet and using apps more. They’re using smart phones to access information, education and entertainment, and, doing so through apps. App downloads are expected to increase 45% by 2022. They also account for 87% of time spent on mobile devices. The shift is significant. Adapting to visitors' online behaviour change is an opportunity for museums to attract and sustain new visitors both in-person and virtually through digital applications. Data on Museum Apps The data on museum app usage is pretty thin, but a report by Colleen Dilenschneider who collects and analyzes data for cultural organizations describes museum app usage in 2017 and 2019. It reveals low usage rate for museum apps in comparison to other media for visitors planning a museum visit (chart below). It also reveals that museum apps don’t deliver higher satisfaction levels compared to other information sources during an on-site experience. What’s a Museum to Do? Should museums even bother with apps given the data that suggests low usage rates? YES they absolutely should. Museums can’t afford to ignore the shift towards app and mobile usage and not dig deeper. Below are factors I suggest contribute to low satisfaction levels, along with a deeper dive into the fundamental problems with museum apps in general. Why Most Museum Apps are Brutal Though it sounds harsh, the majority of museum apps stink—I’m not the only one who thinks so. Just read customer comments on any number of museum apps on the app store—people are pretty blunt; comments include, “horrible”, “does not work with AirPods”, “crashes”, “not worth it” and more. Factors impacting satisfaction include: technical issues, ‘official’ apps versus those developed for profit by outside parties, app design that is poor and/or not intuitive, apps lacking key information like address, admission info, etc. Another issue, most museum apps aren’t integrated into the museum’s strategy—they’re not promoted in museum materials, on the website, or inside the museum. This disconnect affects adoption rate and sustainability.  Screenshot American Natural History Museum's app. It says 'official' in the title--helpful for differentiation over third party apps. Screenshot American Natural History Museum's app. It says 'official' in the title--helpful for differentiation over third party apps. Fundamental Problems ‘Official’ vs Not Some apps are not developed by the museum but by a third party—typically for profit. These apps appear to be the museum’s official app, but aren't. This can create problems, one being that the integrity of the museum might be compromised. The British Museum in London for instance, doesn't appear to have its own app, but there are at least four developed by outsiders. All offer in-app purchases; most have poor customer reviews (see image gallery). Some museums that have their own app, as in the case of the Louvre and The Getty, but are competing with others. There are at least two apps marketed to Louvre and Getty visitors that are developed by outside companies. The American Natural History Museum addresses the problem by stating "official" in the app's description directly beneath the app's title. This is helpful. Technical Barriers Technical barriers are significant, they include battery drain (mostly for navigation when visitors’ location is tracked on their phones), downloading app content which takes up storage on the phone, crashing and freezing, and audio tours only working with plug in earbuds. Finding the museum’s app in the app store is another barrier— apps that don’t include the museum name creates confusion (one example is Cleveland Museum at Art's app named 'Artlens'). Purpose (?) Apps are typically designed for two purposes either for visitors to, 1) plan a visit: getting information on hours, fees, current exhibitions, parking, events, etc., OR, 2) for the museum visit: navigating within the museum, self-guided tours, exploring the galleries, and audio guides. A handful do both. Most do neither well. Few apps provide a digital experience designed to go beyond the visit. This (third) category presents an opportunity for museums to sustain engagement by providing a education or entertainment to visitors who have already visited, or are interested in the museum. A Disconnect There’s often a disconnect between what’s offered digitally via the museum app and the in-person experience. Usually there’s no mention of the app on museum materials (e.g. maps), signage, or on museum exhibit labels. Even within museums "planning a visit [web] pages", apps are rarely mentioned. Image gallery below with screenshots of select museum apps and visitors comments.  Screenshot of the Louvre app; developed by Louvre yet offers 'in-app purchase'; not consistent with most museums offering their app for free Screenshot of the Louvre app; developed by Louvre yet offers 'in-app purchase'; not consistent with most museums offering their app for free Review of Museum Apps I rate the following apps on: ease of use, quality of content, and educational/informational value on the three dimensions mentioned: 1) planning a visit, 2) in-museum experience, and 3) post-visit or digital exploration. "Needs Improvement" British Museum: No official app available. For a museum of this scope, size and ranking, I’d expect the museum to have its own app, more so given that other developers have jumped in the fray with poor quality apps that appear to be ‘official’. Explorer, American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), New York City: Kudos to AMNH—they have an ‘official’ app and make it clear. Explorer seems effective for an in-museum experience with location based guidance. It includes a robust section on amenities. The big drawback—it lacks any information on planning a museum visit—it doesn’t even include the address of the museum (!), directions, or the hours. However you can purchase tickets. Overall it’s a huge miss. Reviewers also complain about battery drain due to location tracking. My Visit to the Louvre, Louvre, Paris. It appears to be the official app; it focuses on the in-museum experience. But it includes an in-app purchase for the audio guide. This is a poor decision on the Louvre’s part—it seems stingy and doesn’t align with other museum practices. Charging visitors for the audio guide who download the official app creates a barrier to engagement; it's also confusing given several apps by ‘unofficial’ developers all with in-app purchases. Artlens by Cleveland Museum of Art. A fairly good app designed for the in-museum experience, but there are issues. Though the tours are its best feature (there are several including some designed by visitors), it’s not intuitive. One section on the app titled ‘YOU’, is designed for the user to add favorite works of art, though instructions are vague. Apparently you can add works “from the ARTLENS Wall”, but it’s not clear where the Artlens wall is. The app also doesn’t much value for planning a visit—there’s no address, directions, or details on admission, though it does display hours and events by day. Another downside—it takes up a big chunk of storage space—217.5 MB. It's far more than the ask BKM app (rating below) which takes up only 18.3 MB. Even Instagram is far lower at 113.5 MB.  Screenshot of 'home' page from Getty 360 app. Clicking on the image takes users to a screen with a detailed description of the event or exhibition. Screenshot of 'home' page from Getty 360 app. Clicking on the image takes users to a screen with a detailed description of the event or exhibition. ‘"Very Good" Getty 360, J. Paul Getty Trust, designed for two locations, the Getty Center and Getty Villa. A very good app for planning a visit to the Getty with information on both locations including events, exhibitions, and detailed information on amenities including restaurant menus. There’s also an ‘About the Getty’ section and a downloadable map. Getty 360 is great for the pre-visit, though it could benefit with a function to search the collection, or include a collection highlights. Art Institute of Chicago, the Art Institute of Chicago. A good app geared to the in-musuem experience; there are over ten audio tours that are well done. There’s also a punch-by-number audio guide for the permanent collection. However you need plug in headphones to hear the audio. The ‘Events’ section is good with a calendar view. But the info section is weak; a ‘Become a Member’ banner displays at the top of the information page before the museum information. Museum information is minimal; only the address and hours are listed. Navigating within the app is poor. Overall the app is very good for in-museum experience, but poor for planning a visit. It has potential for a digital experience with its offering on current exhibition tours.  Screenshot of home screen from LACMA's app. Very user friendly, intuitive. Screenshot of home screen from LACMA's app. Very user friendly, intuitive. "Excellent" LACMA, the Los Angeles County of Art. It hits all three criteria; plan your visit with comprehensive information including an event calendar. It supports an in-visit experience with an audio guide, descriptions and directions to current exhibitions, a map with amenities, and my favorite—a search the collection feature. Best of all there are the detailed descriptions of current exhibitions that include excellent overviews and videos. LACMA app also works well for a digital experience. Exceptions: some reviewers mention the app freezes; you need separate app for a digital membership card, and you can’t purchase tickets from the app. 'Outstanding': The Future of Museum Apps askBKM by Brooklyn Museum takes visitor engagement to a new level with it’s award-winning ASK app. Not only does it have the features for planning a visit (there is a section that takes users within the app to the museum’s mobile website), but it encourages dialogue between a museum engagement team that includes art historians, educators and curators. Visitors can, “ask questions, share insights via live one-on-one texting” according to the Brooklyn Museum’s website, and “It’s easy and fun, and you’re in control the whole time."  Recommendations Should museums have their own apps? This question reminds me of the time when Facebook (FB) came on the scene and organizations were considering whether they should have a FB page or not, as I said then—it’s not a matter of should, but a matter of when. It's the same with museum apps--it's not should we, but when should we. My advice for museums who plan to, or are in the process of building an app:

I hope I have provided some ideas for museum practitioners and visitors; in the meantime I’ll continue trying out new museum apps and write an update post in the coming months. Note: All app screenshots appearing in this post are from Apple app store |

Museums for Real is a blog with insights and ideas on how to make museums relevant and enjoyable for everyone.

|