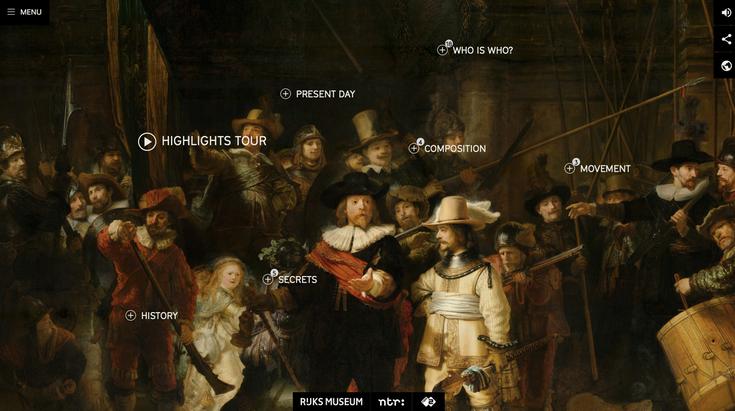

Rembrandt (1660). At the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Rembrandt (1660). At the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. I tried to find an online exhibit on Rembrandt given a ‘wealth of museums’ according to the Art Newspaper, around the world are celebrating the ‘Year of the Rembrandt’ as the year 2019 marks the 350th anniversary Rembrandt’s death (Luke & Da Silva, 2019). Other than a rather static virtual exhibition sponsored by a group of museums in Southern California, I couldn’t find one—so I created my own. Though there are several terrific exhibits to visit in person, including at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam with its year long celebration of events and exhibitions, and at The Met, Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces, and Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt at the Saint Louis Museum of Art, my online exhibit is the next best thing. I created ‘Celebrate Rembrandt’ online exhibit using a variety of dynamic media which allows you to enjoy a selection of Rembrandt’s works and learn about this Dutch Master from the convenience of your desktop or digital device. It includes a selection of excellent (and brief) videos, images, and an interactive media piece that explores one of Rembrandt’s most famous works, The Night Watch. But First, A Brief Background of Rembrandt Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn born in 1606 known as ‘Rembrandt’, was one of the most innovative and greatest artists of his time, and the most significant in Dutch art history. Rembrandt created works in three mediums—painting, drawing and etching, that included self-portraits, landscapes, nudes, ‘tronies’ (paintings of character studies often with exaggerated expressions). His etchings created a new category of enduring works (prints) which transformed printmaking into a legitimate art form (below is a terrific video that shows how he made his etchings). He also introduced a new brushstroke technique consisting of a rough and coarse appearance, described in Dutch as ‘grof mania’ (later Van Gogh took this technique to a new level). His textured brushstrokes differed (drastically) from the smooth, fine painting of the time. Also of significance are Rembrandt’s self-portraits; he painted many, which left us with a visual biography that captures Rembrandt in a series of realistic and frequently unglamorous poses. Rembrandt lived in the Dutch Republic (now the Netherlands) and mostly in Amsterdam for the duration of his life, never traveling to study in Italy or elsewhere as many of his contemporaries had. He worked as an apprentice under two artists for brief periods, eventually opening his own studio and taking on students. Rembrandt’s talents were recognized early on which led to several patrons, though his success is also attributed to connections of his wife's family which benefited Rembrandt greatly. He married Saskia van Ulyenburgh in 1634, and moved into a newly built (expensive) home in an upscale neighborhood in 1639. And though Rembrandt earned a good living, his living expenses were onerous; he was known for living well beyond his means. He struggled financially for most of his life, and died a poor man in 1669. Two Rembrandt Masterpieces The Night Watch (1642) One of Rembrandt most famous works is The Night Watch, on view in the Rijksmuseum. It’s considered one of Rembrandt’s most significant works not only because of its size, but because of how he depicted a militia, which was typically painted as formal and static, yet Rembrandt created a dynamic scene, with action and interesting figures including a young child. The work was commissioned by the musketeer branch of the civic militia; it was finished in 1642. The painting is so enormous that the Risksmuseum had to build a custom gallery for a fitting display in a recent renovation. In 1715, when the painting was moved to Amsterdam Hall, it was trimmed on all four sides to accommodate the painting in it’s new location. The trimmings have yet to be found. Click on The Night Watch image below to explore the painting. Return back to this webpage to continue with the exhibition.  Click on the image: it will open in a new window and take you to an interactive media on the website of the Rijksmuseum. Explore by clicking on the ‘Start’ button; start with the ‘Highlights Tour’. Click on the image: it will open in a new window and take you to an interactive media on the website of the Rijksmuseum. Explore by clicking on the ‘Start’ button; start with the ‘Highlights Tour’. Old Man in Military Costume (1630-31) This is is marvelous work, considered a tronie (character study). Just look at the expression of the man’s face and how Rembrandt’s technique created his expression, and the ostrich plume on his hat. Most interesting is the discovery of what’s under the painting, which was discovered with x-ray fluorescene technology. There’s another figure underneath, which a conservation team at The Getty Research Institute reconstructed. Click on the Old Man in Military Costume image below (it will open in a new window on a different website) to read about the painting's analysis, and scroll down the page to view the re-constructed image and the machine used for scanning. Rembrandt as Printmaker Rembrandt created a new genre of art with his etching technique, known as printmaking. I never was clear on how prints were made in Rembrandt's time—the video by Christie's describes the process beautifully (and briefly). His prints transformed how printmaking was viewed—which was into a legitimate art category. His contemporaries at the time were duly impressed with his etching ability, critics even suggested he had a ‘secret method’ all his own that he didn’t even share with his students. Rembrandt made approximately 290 plates, of which 79 exist today. Interesting is their size; the plates were small, none larger than 21 by 18 inches, most the size of a postcard. Video: Rembrandt: Pioneer Printmaker (1:52 minutes) Video: How Rembrandt Made His Etchings: Christie's (4:08 minutes) To learn even more about Rembrandt’s prints, visit this link to an essay by the Met Museum by Nadine Orenstein, and this article by Ed de Heer. Self Portraits Rembrandt painted, drew and etched, 50 magnificent self portraits, and even though there are approximately 90 that exist, not all are attributed to Rembrandt; research reveals that several were painted by Rembrandt’s students—he had them copy his portraits as part of their training. Rembrandt created self portraits starting in his early 20s up until his death at the age of 63. Some of his portraits show him in unflattering poses, such as Rembrandt with an open mouth, messy hair, a surprised expression and even as an older man complete with wrinkles and extra flesh. Video: Rembrandt, Self Portrait (3:55 minutes) To learn more about Rembrandt’s self portraits, see Rembrandt: Selected Self Portraits at rembrandtpainting.net. I hope you enjoyed 'Celebrate Rembrandt' online exhibit. Below I've pulled together a selection of sites to further explore Rembrandt's works, this Dutch Master and most significant artist of all time. Enjoy! More to Explore Online

List of Museum Exhibitions

0 Comments

Gallery featuring exhibition 'Fashion Redefined: Miyake, Kawakubo, Yamamoto' at Newfields. Garments displayed on mannequins mounted to a runway-type platform. Gallery featuring exhibition 'Fashion Redefined: Miyake, Kawakubo, Yamamoto' at Newfields. Garments displayed on mannequins mounted to a runway-type platform. I recently saw the exhibit, ‘Fashion Redefined: Miyake, Kawakubo, Yamamoto’ at the Indianapolis Museum Art (now called Newfields). The exhibit was on a second floor gallery, adjacent to the European and American Painting and Sculpture Galleries that feature some of my favorites works of Van Gogh, Gaugin and Georgia O’Keefe, Edward Hopper. As I viewed the collections displayed on mannequins, it didn’t feel much different than when I engage with works of art in the other galleries. Yet after pondering the questions later, 'is fashion art' and 'does fashion belong in a museum', and reading what others had to say, I reconsidered: perhaps fashion isn’t really art at all and might belong in a more obscure gallery, or not belong at all. I review here not only the exhibit, but also the idea of fashion as art and its place (or not) in an art museum.  Designs from Kawakubo collections including the blue dress on far right from her controversial 'Bump' collection Designs from Kawakubo collections including the blue dress on far right from her controversial 'Bump' collection The Fashion Redefined exhibit consists of pieces from Newfields collection of Japanese designer fashions that the museum has been collecting since 2009, as well as loans from private collections. The featured Japanese designers were part of a group who arrived on the Paris couture fashion scene in the 1970s and 1980s, and shook things up in the fashion world. These designers not only infused Japanese aesthetics into their designs with clean lines and a focus on minimalism, but challenged the female silhouette—that hourglass figure (or the skinny hourglass figure) that haute couture fashion liked to celebrate. One of the designers, Rei Kawakubo, really disrupted the status quo with her collections that were viewed as gender-neutral, with loose-fitting garments, frayed hems and dark colours. Another collection of Kawakubo’s, the, ‘Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body’ collection, also known as the ‘bump’ collection was another sensation (a few are featured in the exhibit--see blue dress far right in image below). These I found most intruging. So did Paris though not in a good way, they were appalled that these bumps purposefully built into garments, appeared in all the wrong places—they made hips, buttocks and even tummies looks bigger! How dare Kawakubo do so? I found it refreshing. Other interesting garments were four sheath dresses featuring works of art by designer Issey Miyake. These were part of Miyake’s 'Pleats Please Guest Artist Series'. The dresses, were literally, the artist’s canvas’. Miyake chose artists who created art works specifically for the pleated sheath dresses. One off white dress, features a work by Cai Guo-Quiang who used gun powder explosions to create an image of a dragon which was then photographed and printed on flat fabrics before it was pleated (image below).  Dress from 'Pleats Please' collection by Issey Miyake with guest artist Cai Guo Qiang, who used gunpowder explosions to create images of dragons Dress from 'Pleats Please' collection by Issey Miyake with guest artist Cai Guo Qiang, who used gunpowder explosions to create images of dragons Is Fashion Art? The exhibit was well done; the fashions intriguing, the exhibit labels interesting, even thought-provoking. Was this exhibit much different than traditional art exhibits of paintings or sculpture? I did a bit of digging to try and find out what the experts, artists, fashion designers and museum professionals had to say. Overall there's a lack of consensus. Some consider fashion, when in museum at least, like a glorified store window, while others consider fashion similar to decorative arts like ceramics, or jewelery. Others say fashion is not art and doesn’t belong, as fashion is interactive—it requires an active participant—a person wearing the garment. Fashion designers have strong and contradictory views. Designer Jean Paul Gaultier famously said in 2001 “Fashion is not art. Never” (Cathcart & Taylor, 2014). Other designers concurred, including Prada and Marc Jacobs. Artists of traditional mediums weighed in on the discussion and suggested that fashion belongs in its OWN museum, so fashion could be "put into context". Their argument—fashion takes gallery space away from ‘real’ art (Cathcart & Taylor, 2014). My guess is that some museum curators would agree with this argument. Attendance at Fashion Exhibits More importantly though, we should consider what museum visitors think. And if we use attendance numbers as a benchmark, it seems that museum-goers love fashion exhibits—in a big way. The most visited museum exhibit worldwide in 2018 according to the Art Newspaper’s annual museum-visit attendance survey, was a fashion exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination with about 1.7 million visitors. The show, featuring haute couture fashion with religious works of art, was a smash hit—the most visited exhibit in history of The Met! It beat the #1 show of all time at The Met, the 1978 King Tut exhibit, Treasures of Tutankhamen. It also beat out the Mona Lisa Exhibit, when she was on view at the Met in 1963 (with just over a million visitors). Not only that, more than double the number of visitors want to see Heavenly Bodies than another exhibit at the Met that was going on at the same time--Michelangelo in the Divine Draftsman and Designer. Yet not all people agree that fashion belongs in a museum. After reading a selection of reader comments in response to a 2014 article, 'Does Fashion belong in an art gallery', you’ll see what I mean, for example, “…a lot of so called fashion should be in the trash can not in museums”. The comments goes on. What’s Going On Here? Still, museums can’t ignore visitor attendance numbers, discouraging as they may be for artists and museum professionals, that fashion exhibits attract more visitors than traditional art exhibitions. The overwhelming numbers are telling—the response suggests that visitors, (and new visitors who might never have set foot in a museum if not for fashion) find fashion approachable, relatable, interesting and fun. The attendance numbers alone create a strong argument that fashion does belong in an art museum. Perhaps museum professionals need to think differently about what art is, and consider that fashion goes beyond telling a story about how people dressed in a culture or time period, and is thought-provoking, challenging, engaging with potential to change people’s thinking just as traditional art does. What do you think? Sources:

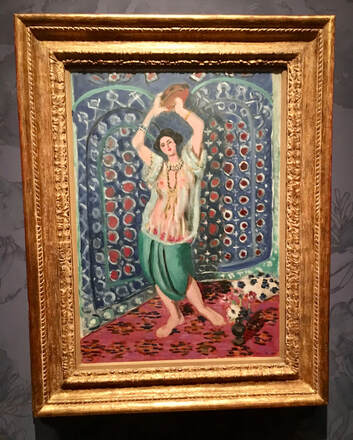

'Odalisque with Tambourine (Harmony in Blue)' by Henri Matisse' (1926) photo, from Norton Simon Museum 'Odalisque with Tambourine (Harmony in Blue)' by Henri Matisse' (1926) photo, from Norton Simon Museum I recently visited the small, but impressive collection of eight paintings in the Matisse/Odalisque exhibit at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. The exhibition, showing until June 17, features four works of 'odalisques' that Henri Matisse painted over his career, as well works of the same subject by Picasso, Bazille, and Devéria. It’s a tremendous exhibit—Matisse’s works particularly. His colours and textures make for a gorgeous, visual experience, as does Picasso’s, Women of Algiers, Version I, an interesting and unique painting. My aim with this post is to help readers experience this lovely exhibition online or in person without feeling guilty for enjoying what some consider, politically-fraught art works that represent colonialism and female exploitation with images and ideas that romanticize harems of the ‘Orient’ (a term used by Europeans to refer to North Africa, Turkey or the Middle East during the 19th and 20th century). I also give some background to the works that will help visitors enjoy the paintings that much more, and I cut through the museum-speak of the exhibit labels. What’s the Exhibit About The exhibit’s focus is odalisques, a French term based on the Turkish word, 'odalık' which refers to female slave or harem concubine. Though it’s unlikely that the artists featured in this exhibit actually saw a harem in Turkey (a ‘harem’ being a separate part of a Muslim household reserved for women: wives, female servants and concubines of the male (polygamists) household leaders), they do however paint the female nude using themes from the 'orient' that include harem settings, costumes and textiles as backdrops. To appreciate the works in the exhibit it’s helpful to look at what was happening during the time the artists created the works. Artists typically don’t create in a bubble, but are influenced by current events, politics, cultural trends, even other artists’ works. We can then, view the works in the Matisse/Odalisque exhibit as a reflection of French culture during the time that the artists lived and worked (for the most part which between the late 19th and mid 20th century), which included at the time an interest in ‘oriental’ themes. We can see these themes in Matisse’s works with his use of fabrics, costumes, and the settings he created, particularly in Odalisque with Tambourine (Harmony in Blue). It’s a carefully staged scene where his model Henriette, (a professional model employed by Matisse) wore clothing that was influenced by Matisse’s daughter, who wore a similar costume to a carnival party when she dressed up as woman from a harem. Notice too the blue North African textile behind Henriette; it’s rich in detail and colour, as is the carpet at her feet. Matisse was known for collecting fabrics and textiles (usually picked up on his travels), which he used not only as backdrops but as focal points in his paintings. Do you think the woman is the focus in Odalisque with Tambourine (Harmony in Blue) or the blue cloth backdrop? One of the earlier works in the exhibit is Jean-Frederic Bazille’s Woman in Moorish Costume painted in his Paris studio in 1869. It takes a different approach, not using the harem setting as a backdrop (except for the sword on the wall and perhaps a tambourine on the floor?) but it focuses on the model, using her clothing as imagery associated with Orientalist themes. Nevertheless, her bare breast gives a sexual connotation.  'Women of Algiers, Version “I”', (1955) Pablo Picasso 'Women of Algiers, Version “I”', (1955) Pablo Picasso I’m a big fan of Picasso's works (not him as a person), and his painting in this exhibit, Women of Algiers, Version I is intriguing. Picasso did a series of paintings on the subject of odalisques, titled Women of Algiers, after Matisse’s death; this version is labeled ‘I’ (there's fifteen works in the series). Picasso was inspired by not only Matisse’s odalisques, but also by an 1834 painting, Women of Algiers in their Apartment, by Eugène Delacroix (see slide show). It’s an iconic harem scene based on Delacroix’s visit to a harem he experience on a trip to Morocco where he was allowed the unusual opportunity (for a European man) to visit within a Muslim harem. Yet when you look at Picasso’s Women in Algiers, Version I painting, it barely resembles either Delacroix’s work or Matisses’. But the painting is interesting; the colours are vibrant, the subjects exaggerated, strange. What do you think Picasso was thinking when he created this? It’s worth pondering; especially when looking at the paintings of the odalisques that inspired him. Clarifying the ‘Museum-speak’ I typically read the introductory labels that introduce an exhibition, and always appreciate those written in straightforward, non-scholarly language. Alas, they are hard to find, and though the Norton Simon is better than most, the exhibit label for the Matisse/Odalisque is a bit cumbersome as follows… “…yet his [Matisse] colorful and daring compositions revel in imagery, and excessively decorative environments that threaten to subsume the female subject altogether. The quest to create a harmonious relationship between figure and ground was one that Matisse paused throughout his career, but in the odalisque, he found a particularly, complex and compelling theme in which to further these ambitions” My 'Non-Museum' Translation Matisse’s paintings are stunning—the colours and patterns Matisse uses in his textiles, the rugs, bedspreads and backdrops are vibrant, bold and gorgeous, so much so they almost overpower his female subjects. Matisse was always striving to create harmony in his works between the subjects and his textured, colourful backgrounds, and even more so when he painted the female figure. The paintings of the odalisques in this exhibit showcase Matisse’s talent, how he was able to create compelling works that highlight his mastery of colour, texture and form. Enjoy! I hope you are able to view this exhibit in person, but if not, I’ve included the link to the exhibit below, along with another link to a previous Matisse exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston that shares other works of Matisse that gives a different perspective.

If you want to go deeper into Matisse and the odalisque theme, see below.

|

Museums for Real is a blog with insights and ideas on how to make museums relevant and enjoyable for everyone.

|